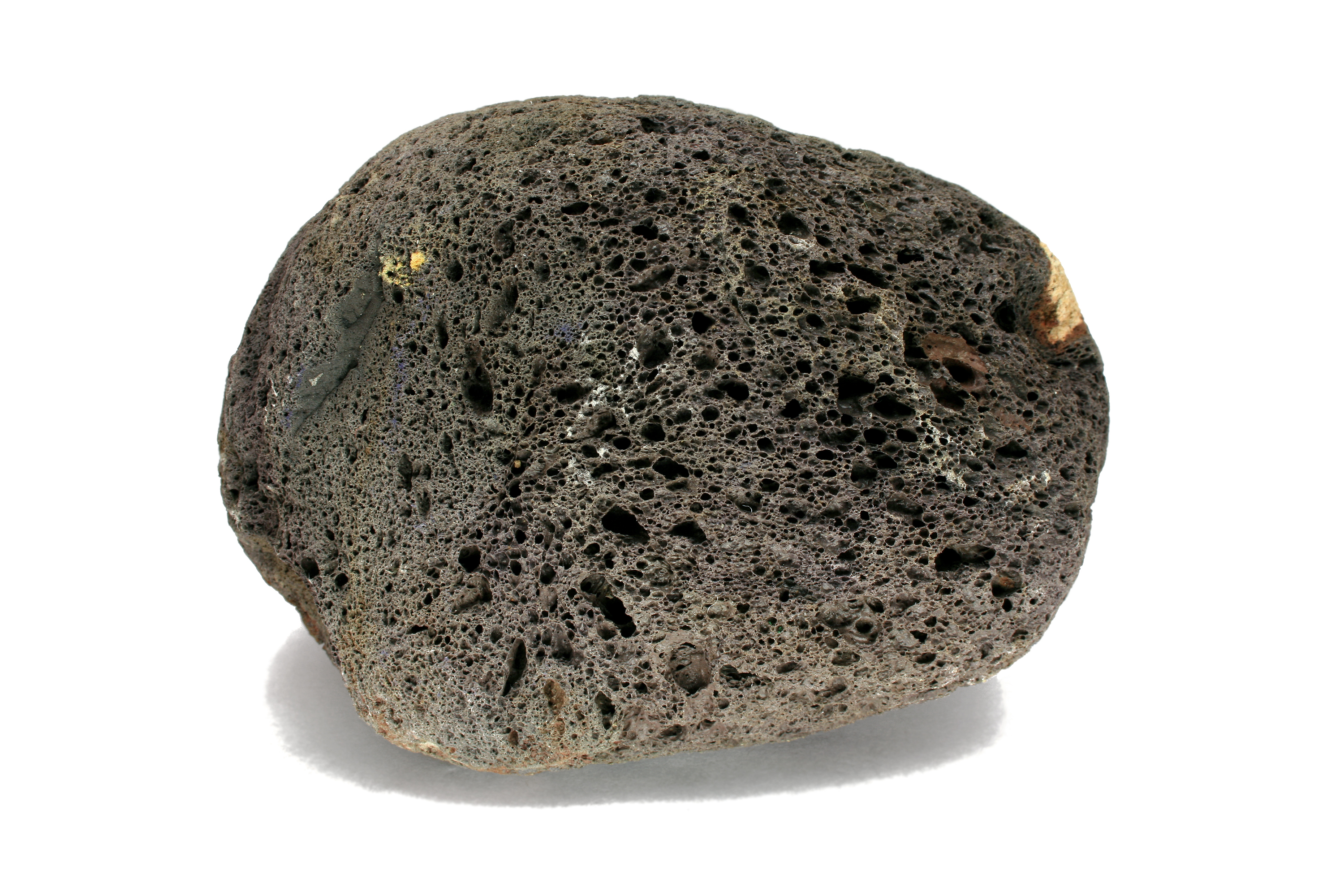

Figure 1.14: Scoria, a type of porous rock formed by expanding bubbles of gas (Copyright © 2008 Jonathan Zander CC-By-SA 3.0)

In the beginning of this chapter I presented the flow of a liquid around clumps as being the main formation process for graph-like toroidal structures. I would like to present three more formation processes; gas expansion, ablation and growth. Gas expansion is when bubbles of gas form in a viscous liquid, ablation is when material is removed to create a toroidal or tree-like structure and growth is a term that you already know.

Think of rising bread.

Figure 1.14: Scoria, a type of porous rock formed by expanding bubbles of gas (Copyright © 2008 Jonathan Zander CC-By-SA 3.0)

The Scoria in Figure 1.14 is not actually as graph-like as it might seem at first glance. It does have hollow bits, but it isn’t particularly toroidal. As I said earlier, toroids have holes in them and these rocks tend to be water proof, not very holy. One type of porous rock, pumice, even floats on water because there is so much air trapped inside! When you think of the physical properties of expanding gas, it is clear why these rocks are rarely particularly toroidal. Gas expands, making bubbles. Those bubbles may then pop. But a popped bubble leaves a crater, not a hole going all the way through a material. Once a bubble has popped, there is no force of expanding gas which would cause another opening to appear on the other side of the crater. Thus, no real graphiness.

However, in concert with ablation, porous rocks may become toroidal. After-all, the bubble walls are very thin and may be worn away quite easily.

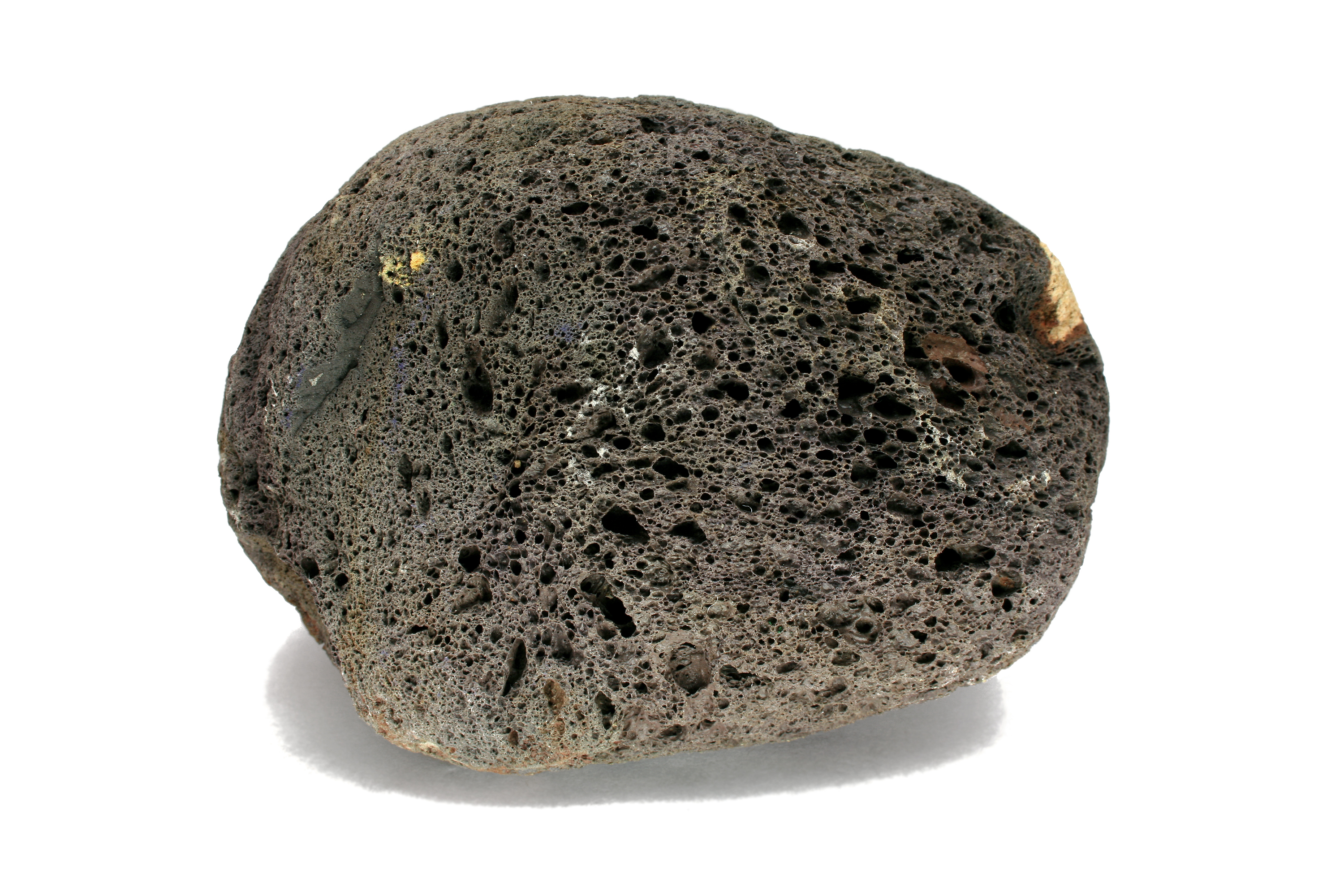

Figure 1.15: A graph-like porous rock, the thin walls of which have become ablated. (Copyright © 2015 Ruben Rubio CC0 Public Domain)

In rare cases, the popping of the bubbles is the direct cause of the graphiness and no ablation is needed.

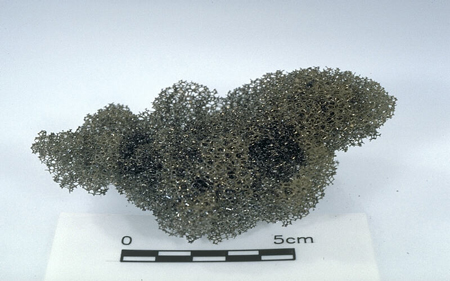

Figure 1.16: Reticulite is a form of volcanic pumice, the bubbles of which have no walls. (Copyright © J.D. Griggs and the US Geographic Survey, Public Domain)

Ablation is when material is washed, corroded, or blown away. This can leave a graph-like or tree-like structure in the following circumstances:

Here are two examples of honeycomb weathering, a complex form of weathering in which calcium is moved within limestone by water, causing it to concentrate in a web like pattern forming a hardened web of rock.

Figure 1.17: Honeycomb weathering, Black Hand Sandstone, Lower Mississippian; Mt. Pleasant, Lancaster, Ohio, USA (Copyright © 2016 James St. John CC-By 2.0)

Figure 1.18: Honeycomb weathering, Watchet, Somerset, Great Britain (Copyright © 2010 Nigel Chadwick CC-By-SA 2.0)

Graph like structures can also grow. Examples include stalactites, icicles, and crystals.